A Memorial Toast to Paul Auster and His Final Novel

Baumgartner proves Brooklyn writer didn’t lose anything off his fastball

It’s been over a year since we lost Paul Auster, the writer and “Patron Saint of Literary Brooklyn” as The New York Times called him. My sister, who outpaced me as a reader in high school and in college, recommended him to me in my early twenties. The timing couldn’t have been better. His postmodern detective fiction, with characters trying to figure out identity and meaning, gave me a lot to think about while I was trying to figure out what I was going to do with my life.

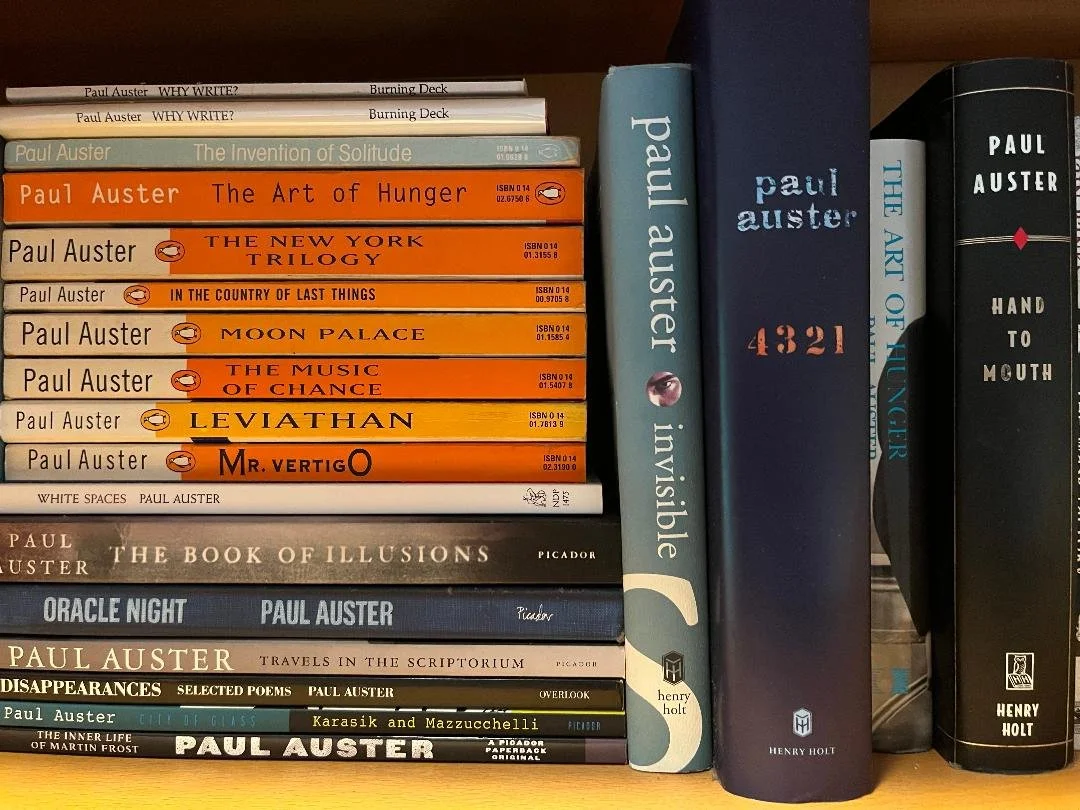

After he published the monumental achievement 4 3 2 1 in 2017, there was a chance we might not have seen another novel from him. It wasn’t bad, quite the contrary—my favorite of his post-Viking Press output, in part due to my affinity for longer stories where structure is critical. Anyway, a friend of mine texted me last year that he’d picked up Baumgartner and, knowing my love for the author, asked if I’d read it. Had zero clue it even existed, shame on me, but I eventually bought it, put it in the pile in my nightstand, and waited until the time was right.

Recently, I needed a dose of what Auster delivers to help me reset. Tore through the 202-page paperback on a trip to Florida in three sittings, two of which were on the plane. It’s smooth and absorbing, his prose always flows—no turbulence in the words, unlike with the flight home. So much hallmark Auster here, too: writerly people; written pieces and poems nested within the larger framework, with flashback galore; New Jersey, the state he was raised in; and baseball, reference to the Mets included. Auster’s autofiction is alive and well, with enough differentiation to capture a semi-newish vibe that has, as it turned out, a hint of finality.

Sy Baumgartner is a professor of philosophy at Princeton whose wife Anna, the absolute love of his life, died in a random swimming accident nine years earlier. That’s the setup. He’s getting older, now 71, and lonelier. He suffers from grief and guilt and struggles in the wake of her absence. His writing puts wind in his sails, but he has a habit of holding onto things. Then again, this is tricky business determining the right moment to let something go…or, perhaps, to set it free.

Auster prioritizes existential debate over action, making the first chapter a slight anomaly despite some nice internalizing. Sy is sidetracked around his house, burns his hand on a pan, and tumbles down the decrepit basement stairs. Supporting characters come and go. Before returning to mild action in the fifth and final chapter, the surf-and-turf portion of the book is cooked in full Auster fashion: backstories covering Anna and Sy’s romance and relationship from the start through her freak tragedy, details about parents and family and memories that carry intimate meaning, the woman he was with after Anna and her impact. Even in a short novel, structure is vital in how information is dispensed and how characters are developed, and in Baumgartner, each moment propels you to the next, connections form in an effortless way. As usual with Auster, coincidence doesn’t exist.

Endings, optimistic or otherwise, can be difficult to conceive, even harder to execute. It’s often more about editing than the writing or whatever the audience wants. I’m sure many would’ve enjoyed fifty more pages—the runway was there for further scenes with Anna and Sy, as well as a final showcase of her writing but from a fresh, younger person’s perspective. Here’s the deal, though: The action and the lesson that needed to happen had already happened. We know the outcome beyond that because we can feel it, visualize it—it’s not sentimental, just real. Maybe you disagree, that you don’t, or won’t, think this story of grief in later years was formally resolved, or closed. But at the very least, the ending is a fitting way for Auster and Sy to sign off before the novel took on unnecessary weight.

Auster will go down as many things, but he’s a New York City storyteller to me. Even if the book is set in a place other than NYC, he has that mindset. Baumgartner was a satisfying excursion. Not his greatest novel, not by a long shot, but I smiled upon finishing it and it’s made me think since. Although I now hope for unreleased archival material, I do always have the option of rereading Leviathan or Ghosts, stories that also remind me to look inside myself and to look myself in the mirror while trying to figure out identity and meaning into my fifties.

The message constantly reverberates. I have Paul Auster to thank for that generous offering.